Arif Salimi

During the height of the revolutionary movement” Women, life, freedom”, a video depicting threats issued by security forces against the residents of Ekbatan neighbourhood in Tehran surfaced, inciting strong reactions. In the video, the voice of a commander from the Islamic Republic’s security forces can be heard addressing the residents of Ekbatan through a loudspeaker, saying, ‘If necessary, we are ready to decapitate our wife, children, and our honour for the protection of this system.’

Simultaneously, numerous Iranians shared the video as compelling evidence of the cruelty and criminal tendencies exhibited by the forces affiliated with Khamenei. Many drew parallels between the security commander and ‘Babak Khorramdin’ and certain leaders of the Islamic Republic, including Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, the Secretary of the Guardian Council, who were implicated in the killing of their own children.

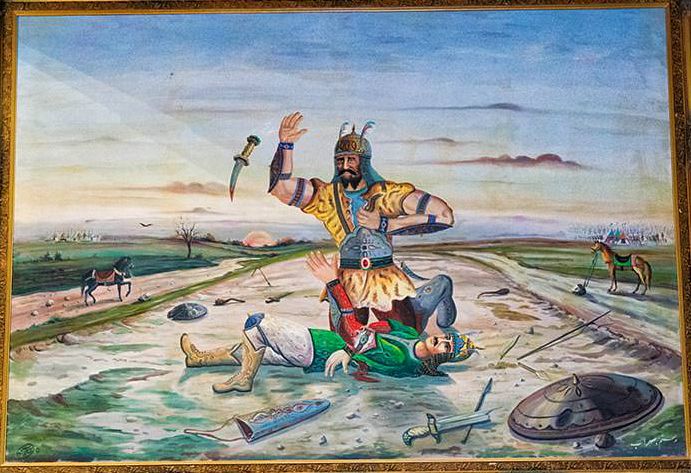

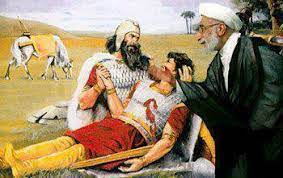

Rostam the Hero as Janati of the Time

Much like the statements of that commanding officer within the Islamic Republic, a few years ago, a patriotic poet and thinker spoke eloquently in the poetic style, drawing inspiration from the language of Rostam, the legendary hero of Iranians and a symbol of national pride. Ali Reza Shajapour, a poet, Shahnameh reciter, and former Iranian diplomat (apparently during the Shah’s era), can be seen in this video expressing his deep-seated concern about how to narrate the conclusion of Rostam and Sohrab’s story to his seven or eight-year-old son. He grapples with the dilemma of explaining to his son that Rostam, the Iranian hero, took the life of his own son with a sword. In an attempt to justify Rostam’s actions to his young son, he pens a poem in which Rostam acknowledges that he killed Sohrab “knowingly” for the sake of preserving the flag and the Iranian lineage. This poem by the patriotic Iranian diplomat, poet, and intellectual essentially rebukes the words of that commanding officer in Ekbatan city, Tehran. Both instances reflect the willingness of a father to sacrifice his son(s) to uphold the “system” or the “nation” he identifies with as a devoted soldier. In essence, what that commanding officer of the Islamic Republic proclaimed in Ekbatan city aligns with the actions of Rostam, the renowned Iranian hero whom every commander and soldier aspires to emulate.

Filicide extends beyond the realm of mythological tales and Rostam. Throughout Iran’s history, numerous leaders have committed filicide, some of whom are still hailed as “great” and “noble” figures within Iranian culture. Notable instances of child-killing include Shah Abbas Safavi and Nader Shah Afshar, two iconic figures in Iranian nationalism. Nader Shah, renowned as the conqueror of India, infamously gouged out the eyes of his own son, Shahrokh. Similarly, Shah Abbas Safavi, also known as “the Great” and commemorated with a port named after him in southern Iran (Bandar Abbas), took an active role in filicide. In addition to murdering his eldest son and successor, Mohammad Mirza, Shah Abbas the Great also incarcerated at least two of his other sons in ‘the Castle of Death’. even surpassing Akbar Khoramdin—a man detained a few years ago, along with his wife, for the murder and dismemberment of their son, daughter, and son-in-law.

Astonishingly, even within the current Islamic Republic system, several prominent figures such as Mohsen Rezaee, the former commander of the Revolutionary Guards, and the current secretary of the Expediency Discernment Council, Mullah Hassani, the former Friday prayer leader of Urmia, Mohammad Mohammadi Gilani, the early post-revolutionary Sharia Ruler, and former secretary of the Guardian Council, are either murderers or suspects in their sons’ deaths. Furthermore, Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, the current secretary of that council, and Hassan Rouhani, the former president, are also implicated in the killing of their sons. Even in the case of Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, there are plausible rumours that he himself was responsible for the death of his eldest son, Mostafa. At the very least, there is no doubt that Khomeini referred to his son’s death as a ‘divine hidden mercy’.

As long as Rostam remains the champion and hero of Iranians, can we ridicule these officials and statesmen for the murder of their sons, all of whom claim to be acting in the interest of the system, the homeland, and the flag? Generally, in a culture where Shah Abbas Safavi, Nader Shah Afshar, and Rostam are esteemed historical and mythological heroes, why should one condemn Ayatollah Jannati, Mohsen Rezaee, or the commander of law enforcement in Ekbatan? Do not Rostam, who, much like Ayatollah Jannati, took the life of his son in order to “protect” the “Kayanian throne” (the Shah’s regime/Islamic rule), serve as the role model for that law enforcement commander in Tehran? Or for that poet and patriotic diplomat who not only “sacrifices his life” for the sake of “this Kian” but also has no hesitation in committing child patricide?

The purpose of posing these questions is not to exonerate or justify filicide, but rather to draw attention to the idea of whether those historical and mythological heroes were not similar to figures such as Khomeini, Rouhani, Jannati, or Rezaee in their respective eras.

Filicide: a Deep-Seated Tradition in Iranian Culture!

Unlike Hellenic and Semitic cultures, Iranian culture is marked by a strong tradition of filicide. Even today, this culture regards being sacrificed by a father or sacrificing oneself in a father’s name as a noble act.

In Greek mythology, the story of Oedipus, often considered a parallel to the Rostam myth in Persian culture, where a son kills his father, occasionally symbolizing generational rebellion against the elder generation, has been the subject of extensive discussion in literature. Yet, less focus has been given to the contrast with Semitic cultures (Arabic and Hebrew), where, in contrast to Iranian culture, children’s rebellion against their fathers is even more prominent than in Hellenic culture.

Abraham, the patriarch of the three Semitic religions, celebrated by Muslims for his refusal to sacrifice his son (Eid al-Adha), also embodies a son’s rebellion against his father[1]. He is depicted as an iconoclast in the religious myths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. His rebellion commences with the destruction of the idols crafted by his father/uncle, and later, he rebels against Nimrod, who holds a godlike or patriarchal status. Moses, the Jewish prophet, defied his father or adoptive father, Pharaoh, and ultimately drowned him in the sea. The uprising, revolt, and wars involving the Islamic prophet Muhammad predominantly were against his uncles, Abu Jahl and Abu Lahab, who, in the absence of his father and grandfather, assumed a paternal role[2].

In Iranian culture, unlike Hellenic and Semitic traditions, the father figure is revered to such an extent that any form of opposition, even if it’s respectful, is simply categorized as ‘defying the father’ and is subject to severe condemnation. In this culture, bearing a father’s imprint (even when the father is less than exemplary) is a prerequisite for ‘khalef’ status and one’s identity. A son lacking a father’s influence is branded an ‘outsider’ or ‘stranger’ (a significant insult in Iranian culture). The father, known as ‘Aghajan’ or ‘Sahib-e Akhtar,’ commands unwavering respect from his children, regardless of the mistreatment they may endure. They are required to kiss his hand and constantly wish for ‘his shadow’ to cast protection over them. In this culture, one of the most egregious moral transgressions is ‘defying the father.’ The sanctity of the father figure is so deeply ingrained that certain children, like Sohrab, might even, without any complaint, go to their deathbed to preserve or elevate their father’s honor

The Killer Fathers, the Foolish Sons

In the mid-1990s, Ahmad Rezaei, the son of Mohsen Rezaei, who had recently fled Iran and sought refuge in the United States, appeared as a guest on the Voice of America’s weekly program titled ‘Roundtable with You’ (the first prominent mainstream media television show outside the country). During this program, he openly characterized all high-ranking officials of the Islamic Republic as corrupt and criminal, with one significant exception—his own father, Mohsen Rezaei. Ahmad Rezaei reiterated this point multiple times, consistently excluding his father from the list of corrupt officials. Throughout the broadcast, he made a determined effort to absolve his father from the allegations of corruption and crime that, according to him, had plagued the Islamic Republic. He even went so far as to suggest that his father’s character, honor, and standing were superior to other officials. He proposed that if his father were at the helm of the regime, the nation’s situation would be far less chaotic. Several years later, in a mysterious incident suspected to involve his father, Ahmad Rezaei was assassinated in a hotel in Dubai. The details of his murder have never been clarified, and to this day, his father remains one of the high-ranking officials within the Islamic Republic.

The image Ahmad Rezaei painted of his father’s role and status within the ‘corrupt, incompetent, and criminal government apparatus’ of the Islamic Republic draws a striking parallel to the story of Sohrab and his renowned father Rostam, as recounted in Iranian mythological narratives. In Iranian mythical tales, it is recounted that Sohrab fought to enthrone his deserving and heroic father, overthrowing the incompetent ‘Kai Kavus’ and placing the ‘Kiani crown’ on his head. Sohrab, who was raised in the land of Turan, had only heard of his father from afar and had never seen him up close. Nevertheless, he believed that no one was as deserving of the Kiani throne and crown as Rostam, and he explicitly told that to his mother. In his quest to place his father on the throne, he asked ‘Afrasiab’ for an army and troops to go to war against ‘Kai Kavus’ forces. Unbeknownst to him, his father was the commander of Kai Kavus’ army; the guardian of the system, and for the sake of its preservation, he did not hesitate to kill his own son.

The stories of Sohrab’s and Siavash’s deaths are among the most tragic parts of Iranian mythological narratives. Sohrab and Siavash were both direct and indirect victims of their fathers’ actions. However, in Iranian culture, neither Rostam nor Kai Kavus are condemned for the murder of their sons[3]. The most poignant aspect of the tragedies of Rostam and Sohrab, along with numerous other instances of filicide in Iranian culture and history, lies in Sohrab’s tragic misconception about his father. Right up until his final moments, he harbored not even the slightest doubt about his father’s greatness, despite the fact that it was his father who had taken his life. As Sohrab takes his last breaths, he utters to Rostam, ‘Should my eminent father learn of this event, he will track you down, regardless of your attempts to conceal yourself beneath the sea’s depths or amidst the sky’s clouds, and he will exact vengeance for my spilled blood.’ Unbeknownst to him, the one ending his life is none other than his own father. Sohrab’s words bear a poignant resemblance to those of Ahmad Rezaei, Mohsen Rezaei’s son, in a radio/television program broadcast by Voice of America.

Our Contemporary Sohrabs

One can discern this similarity in the words and behaviours of many of the current Iranian ‘Aghazadeh’ (children of prominent figures) and ‘Shazdeh’ (princes) who are actively involved in politics, particularly those who advocate opposition to the Islamic Republic.

For instance, Reza Pahlavi, the son of the last Shah of Iran, serves as a prominent illustration. Similar to the legendary Sohrab, he, too, aspires to revive Iran to the ‘era of greatness and glory of his father and grandfather.’ He essentially inherits everything, whether it be material wealth or political influence, from his father and grandfather. His desire is to reinstate the honour of his father, who was labelled as the ‘oppressor of the nation’ during the 1979 Revolution. Like Sohrab, he seeks redemption for his father.

This is equally applicable to Hassan Shariatmadari, the son of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, one of the foremost Shia clerics. Just like Sohrab, Ahmad Rezaei, and Reza Pahlavi, his ultimate goal is to portray his father as an exceptional, blameless figure within the centuries-old Shia clerical institution, which has profoundly influenced ‘Iran’ from the Safavids to the present day. He, akin to Reza Pahlavi, has never publicly criticized his father or taken a stance against his father’s beliefs. In politics, he, like Reza Pahlavi, operates in the shadow of his father, and his most defining characteristic is that he is the ‘son’ of Ayatollah Shariatmadari. It is entirely plausible that he, too, similar to Sohrab, envisions overturning the rule of the clerics and restoring the honour of the clergy and its institution, to which his father was once a cornerstone.

From the offspring of Hashemi Rafsanjani (Fa’ezeh, Mehdi, and Mohsen) to the son of Abdolkarim Soroush, as well as numerous other Aghazadehs in the domains of politics, culture, art, and intellectual thought, particularly among the critics and opponents of the Islamic Republic, we encounter individuals who all hold their father’s affection in their hearts and are reluctant to openly criticize them or ‘oppose their fathers’ in the public.

In the various parts of Iran, within a multitude of regional parties and movements, one can find what are colloquially known as “militant Sohrabs.” These individuals primarily advocate for challenging the deeply entrenched system of the Islamic Republic. What unites them all is a shared belief in the sanctity of their ‘reactionary’ fathers, and they still view opposing their fathers as a source of shame.

Yet, a question arises: does this sentiment hold true for the new generation, the people born in the 1990s who bravely took to the streets to confront the Islamic Republic? Or will this generation carve out a different path for itself this time?

The ‘Woman Life Freedom’ Movement; the Daughter’s Rebellion against the Tyrannical Murderous Father

The 1979 Revolution represented a power struggle between paternal figures, or more precisely, the replacement of fathers by figures like Sohrab. This was a revolution during which, alongside the iconic chant of ‘Death to the Shah,’ another slogan, ‘Greetings to Khomeini,’ resounded. The youthful and educated revolutionary generation of that era, fervently engaged in partisan warfare and climbing embassy walls, shared a singular objective: to depose the despotic Shah, a paternal figure, and replace him with an elderly man whose image had seen in the moon—much like Sohrabs aspiring to replace Kaykaus, the cause of youth’s bloodshed, with ‘Rostam the Hero.’ They successfully ousted the Shah and enthroned Ayatollah Khomeini.

In the early days and months, it became evident that this new patriarch is even more ruthless and tyrannical than his predecessor, taking the lead in incidents referred to as ‘Sohrab killing’ and ‘Siavash killing,’ leaving Rostam and Kaykaus far behind. But does the ‘woman, life, freedom’ movement currently sweeping through Iran constitute a revolutionary challenge to the ‘sacredness’ attributed to the traditional figure of the father in Iranian culture?

In the movie ‘The Leila Brothers,’ directed by Saeed Roustayi, we witness ‘Leila,’ as a daughter/sister in the family, delivering a resounding slap to the old and miserable father who sacrificed her children’s future for his dogmatic beliefs. This single act has resonated deeply with countless girls and women, as expressed on social media.

Produced before the advent of the ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ movement, this film exhibits indicators of a fundamental transformation that has unfolded in family dynamics and parent-child relationships over the past two decades. This transformation is now becoming apparent at the societal, political, and cultural levels. The film serves as the vanguard of a significant ‘renaissance’ and ‘rupture,’ ushering in a cultural, historical, social, and political shift that relegates everything associated with the past to its proper place: history. It seeks to forge a new identity, rooted in radical critique of the past or, ultimately, independent of any reliance on elements from the past.

This generation relegates all historical, religious, and mythological heroes to the ‘past.’ It not only questions figures like Muhammad and Ali, Fatimah and Hussein but ultimately turns back to figures like Cyrus, Darius, Rostam, Shah Abbas, Nader Shah, and Reza Shah, asking questions like, what’s the difference between Chengiz and Cyrus? or wasn’t Rostam, the Hero, an Ayatollah Jannati in his time?

The ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ movement, sparked by the killing of Jina Amini, has heroes like Nika, Hadis, Sarina, Ghazaleh, Donya, Armita, Aida, and others. It is a movement of courageous girls who have risen against the imposition of the veil, a symbol of old-fashioned patriarchy. These young people taking to the streets are not doing it to restore the honour of their fathers, not even for their mothers, but for their “own” freedom. (In recent months, most of the videos showing student protests have been related to girls’ schools). This time, unlike the year 1979, these young girls and teenagers who are the pioneers and leaders of this movement seem to have no faith in neither the Rustams nor even in the Sohrabs who claim to have inherited dignity from their “Rostam Neshan” fathers from afar.

It is said that during the 1979 Revolution, the slogan “Death to the Shah” was only chanted in the final months leading up to the overthrow of the Shah’s regime. However, in the current movement, the 1990s generation, from the very first days, began chanting the slogan “Death to Khamenei” and expressed their displeasure by showing their middle finger to him. At the same time, unlike the 1979 revolution and even in contrast to the protests of 1996 and 1998, they did not shout “greetings” or “long-lived” slogans to anyone.

The 2000s generation, before taking to the streets, has rebelled against the authority of their fathers, or at the very least, their fathers no longer embody that historical role of an Iranian father for them. Daughters mainly address their father as “Dad,” not “Sir,” or even just call them by their first name. Inside their homes, they stretch their legs in front of him and sit without a veil and in pants. They interrupt his speech without any aversion and engage in dialogue using the language of the alley and the bazaar. Many times they have shouted at him and ‘stood against him.’

This is a new generation that no longer wishes to sacrifice their lives for the desires and expectations of their parents. They want to live their own lives, not to please their fathers, and they are even ready to become ‘Oedipus’ for the kind of “life” they desire. This is a generation that no longer wishes to be killed by the father and traditions of their fathers, and if necessary, they will even remove their fathers from their path. Such a generation and daughters are certainly no longer “obedient” and “submissive,” even if they love their fathers.

[1] The relentlessness of Rostam in his pursuit to kill Sohrab through three consecutive battles stands in stark contrast to Abraham’s decision to refrain from the act of killing Ishmael. This contrast underscores a foundational difference between these two seemingly similar Iranian and Semitic myths.

[2] It is worth considering that all three mythological figures—Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad—are recognized as the three founders of Abrahamic religions and share the common trait of being truly “fatherless.” Their fatherlessness is significant when compared to that aspect of the Iranian collective unconscious that still desires “leaders” bearing the symbolic presence of a “father.”

[3] In the narrative surrounding Siavash’s tragic demise, instead of laying the blame on Kai Kavus as the wrongdoer, the finger of accusation is pointed squarely at Sudabeh, who not only happens to be the wife of Kai Kavus but also holds the distinctive title of “father’s wife” to Siavash. This highlights an intriguing aspect of Iranian culturewhere a woman is often implicated in event, even when the father is implicated in the murder of his own child.